The Gamechangers, Part 4: The 1980s Bring Tribal Victory, New Chapter For Local Libraries

By Craig Manning | April 24, 2022

Known for vibrant colors, adventurous fashion choices, big hair, massive blockbuster films, and zippy new wave music, the 1980s are, from a cultural standpoint, one of the most oft-caricatured decades in American history. If you were alive to see Traverse City in the 1980s, you probably encountered many of these iconic trends right alongside the rest of the nation.

But the ‘80s also saw their fair share of gamechanging local milestones that transcended any pop cultural moment, from the establishment of the still-active Bay Area Transit Authority (BATA) in 1985; to the closure of the State Hospital in 1989 – which eventually paved the way for what we know today as the Grand Traverse Commons.

What were the most crucial events of the 1980s for the local history books? Read on to find out.

1980: The Grand Traverse Band wins federal recognition

Any lookback at the history of the region would be incomplete without an acknowledgement that the community sits on land first settled by the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians (GTB). Long before the area was part of Michigan, it was the home of the Anishinaabek, described on the GTB website as a wealthy and respected indigenous nation with trade routes that extended “as far east as the Atlantic Ocean, as far west as the Rocky Mountains, as far north as Northern Canada, and as far south as the Gulf of Mexico.”

Centuries of war and unbalanced treaties gradually stripped the Anishinaabek of its land and its federal recognition as a native tribe and nation. 1980 was the year in which the GTB won that recognition back.

Before and immediately after the Revolutionary War, the Anishinaabek nation occupied the northwest part of what would become Michigan’s Lower Peninsula, as well as the eastern part of the Upper Peninsula. In 1836, though, the federal government approached the indigenous tribes with a treaty. By signing that document, called the Treaty of Washington, the tribes ceded two-thirds of the land that is now Michigan to the federal government. In turn, the treaty was meant to protect the right of the tribes to continue using the lands, including for hunting, fishing, and gathering.

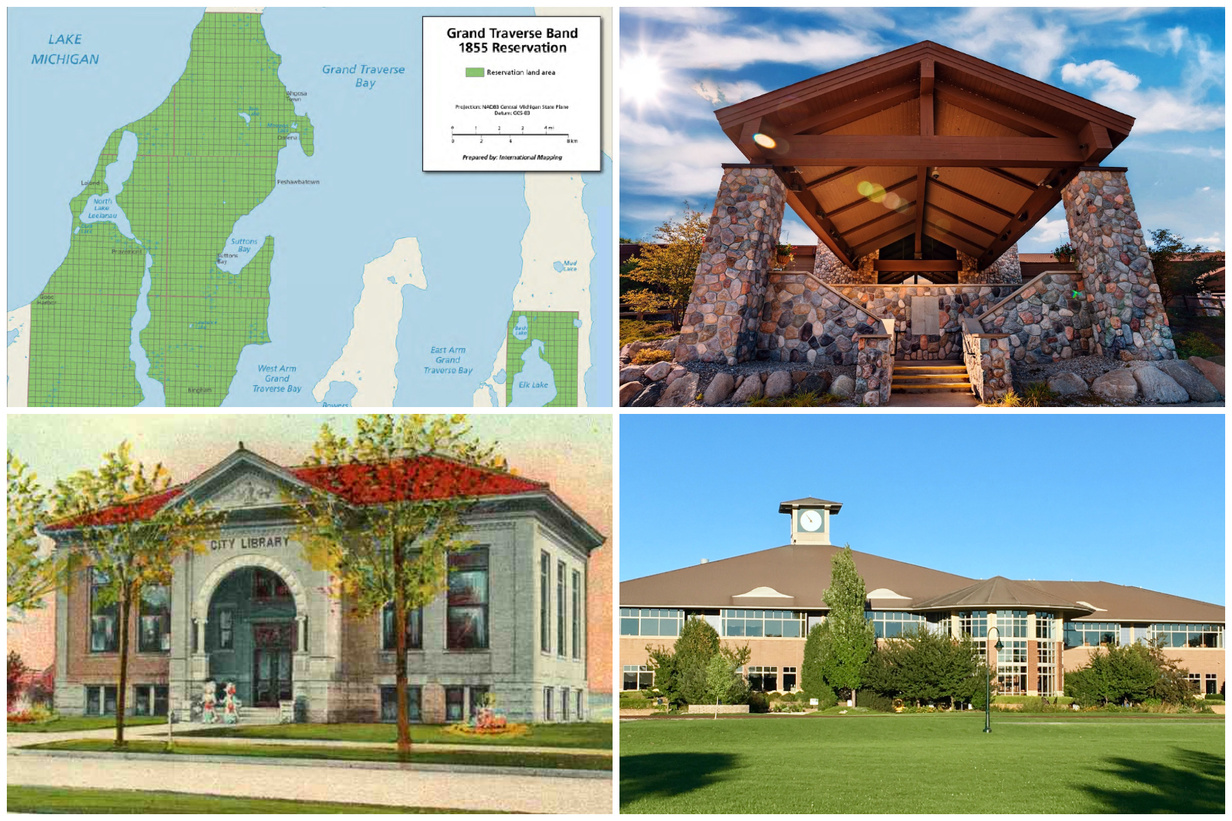

A second treaty, the 1855 Treaty of Paris, asked the tribes to cede “the remaining third of what is now Michigan” to the federal government. “When this treaty was signed, a reserve was established that included most of Leelanau County and a large tract of land in Antrim County,” GTB’s historical account notes. (Pictured, upper left, a map of the reservation land outlined in the 1855 treaty.)

Despite those agreements, the GTB has long held that the U.S. government reneged on the Treaty of Paris by selling off approximately 87,000 acres of the reservation lands to lumber firms and non-native settlers without ever fairly compensating the tribe. In the 40 years following the treaty, the tribe lost virtually all reservation land promised by the 1855 treaty. GTB is still seeking “just compensation” for this land from the federal government.

GTB also “went without any federal or state assistance from a time period shortly after the treaty of 1855 until 1980,” due to the fact that the the Bureau of Indian Affairs “determined incorrectly that the tribe had been terminated by signing the treaty.”

The tribe tried multiple times throughout the 20th century to reestablish federal recognition under the Indian Reorganization Act – first in 1934 and then again in 1943. Both of those applications were denied by the federal government. It wasn’t until 1978 that the tribe began to gain traction with its efforts to restore status as a federally recognized native nation. On May 27, 1980, the federal government finally recognized the GTB, allowing the tribe to draft a constitution, form a government, and more.

In 1983, GTB established an Economic Development Corporation for the purposes of starting and operating its own business ventures. The most consequential of those businesses launched the following year, when the tribe opened the doors of the first incarnation of the Leelanau Sands Casino.

At the time, Michigan law still prohibited almost all types of gambling, but native tribes were starting to challenge the idea that the state had any right to enforce those bans on sovereign tribal nations. On July 4, 1984, Bay Mills Indian Community – an Upper Peninsula tribe – became the first native nation in Michigan to open a casino. Shortly after, GTB established the Super Bingo Palace and Leelanau Sands Casino in Peshawbestown, and casino gaming in northern Lower Michigan was off to the races for the first time. Leelanau Sands took up residence in its current building (pictured, upper right) in May 1991.

1982: TADL is born

By the 1980s, northern Michigan was already home to a slew of well-established libraries. The Traverse City Library, for instance, had been operating in the Carnegie Building on Sixth Street since 1904 (pictured, lower left). Still, it wasn’t until 1982, that the Traverse Area District Library (TADL) system we know today officially formed.

TADL came to be thanks to a joint resolution of the City of Traverse City and Grand Traverse County. That resolution established a federated library system that included not only the Traverse City Public Library, but also the libraries in Fife Lake, Interlochen, Kingsley, and on Old Mission peninsula. In 1983, voters ratified the establishment of TADL and approved an operational millage to support district-wide library services.

It’s thanks to the millage-funded operational structure established for TADL in the 1980s that Traverse City has its current main branch library building on Woodmere Avenue. In 1996, Grand Traverse County voters approved a ballot measure that opened two key doors for the library system. First, voters authorized a 1.1 mill tax levy, which would pay for operations of all TADL libraries for the next 20 years. Second, voters agreed to issue up to $8.5 million in bonds to cover the cost of a brand-new library building. At the time, TADL was outgrowing the 16,000 square-foot Carnegie Building and needed room to expand. The $8.5 million bond provied a way forward.

TADL broke ground on the Woodmere branch (pictured, lower right) in May 1997, with construction ultimately wrapping up in late 1998. The opening gala celebration took place on January 9, 1999, officially kicking off a new chapter for TADL.

In 2019, when the main branch marked its 20-year anniversary, The Ticker learned that the library had over 68,000 active cardholders, more than 388,000 physical items in its collection, and a track record of loaning out an average of 1.2 million items to local patrons every year. Those numbers represented a library triple the size and impact of what TADL was able to accomplish when the Traverse City District Library was housed at the Carnegie Building.

TADL continues to mark new milestones in 2022, including the adoption of a brand-new strategic plan and the forthcoming launch of a long-awaited bookmobile.

Comment